Have you ever wondered what happens when you click on “Run with Coverage” in IntelliJ? Obviously it’s running the tests, but how is it collecting the coverage information?

Let’s create a simple Line Coverage Analyzer in and for Java 🥳

First of all, let’s write a simple example program (see GitHub)

package de.brokenpipe.dojo.undercovered.demo;

public class Demo {

public static void main(final String[] argv) {

final String greeting = "Hello World";

bla(greeting);

bla("to the blarg");

}

private static void bla(final String greeting) {

System.out.println(greeting);

}

}

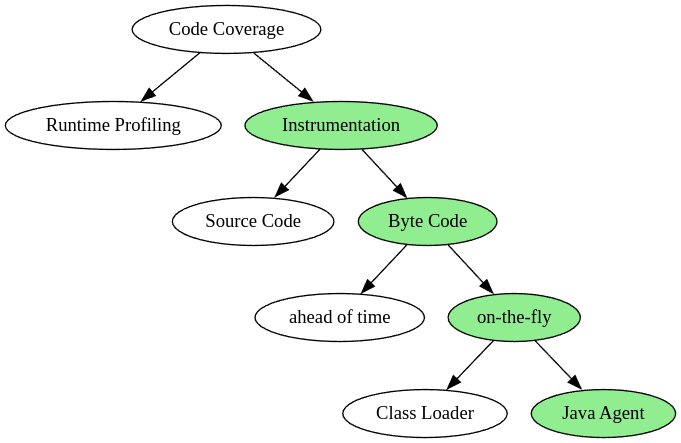

Coverage Collection Options

In general coverage data can be collected in multiple ways. We could use profiling/debugging APIs or instrument the code. Instrumentation can be achieved on both, Source Code and Byte Code level. The latter can be done on-the-fly or ahead of time. The on-the-fly part can modify the Application Class Loader or use special APIs available to the Java Agent.

So what is Source Code Instrumentation?

Let’s assume we would have a static tracking method like this:

package de.brokenpipe.dojo.undercovered.coverista.tracking;

class Tracker {

public static void track() {

// TODO actually track the calling locations here

}

}

… then we would just need to modify our source code like this:

package de.brokenpipe.dojo.undercovered.demo;

import static de.brokenpipe.dojo.undercovered.coverista.tracking.Tracker.track;

public class Demo {

public static void main(final String[] argv) {

track(); final String greeting = "Hello World";

track(); bla(greeting);

track(); bla("to the blarg");

}

private static void bla(final String greeting) {

track(); System.out.println(greeting);

}

}

… and we should be done. Right!?

Obviously messing with the source code doesn’t feel nice. We’d need to re-compile everything, and after all we would need access to the source code in the first place. Also we shouldn’t overwrite the original source code, since the user likely doesn’t expect us to put all these track(); calls there.

We also would need to write a parser for Java Code, that understands which lines have a statement, so we can prepend our track(); call to these. Also considering statements spanning multiple lines.

So given that the Source Code is compiled to Byte Code anyways, how about instrumenting that instead?

Instrumenting the Byte Code

There are multiple tools, that you can use to inspect the Byte Code that’s stored within a .class file. IntelliJ itself has the “Show Bytecode” view action. On the command line there’s the javap tool, that’s part of the JDK. In it’s simplest form we can invoke it with the -c option, so it disassembles the byte code for us. Running javap -c demo/target/classes/de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/demo/Demo.class should print this:

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

Code:

0: ldc #7 // String Hello World

2: astore_1

3: ldc #7 // String Hello World

5: invokestatic #9 // Method bla:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

8: ldc #15 // String to the blarg

10: invokestatic #9 // Method bla:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

13: return

You might wonder what these hash-numbers are!? These refer to the so-called constant pool.

$ javap -v demo/target/classes/de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/demo/Demo.class

Constant pool:

#1 = Methodref #2.#3 // java/lang/Object."<init>":()V

#2 = Class #4 // java/lang/Object

#3 = NameAndType #5:#6 // "<init>":()V

#4 = Utf8 java/lang/Object

#5 = Utf8 <init>

#6 = Utf8 ()V

#7 = String #8 // Hello World

#8 = Utf8 Hello World

#9 = Methodref #10.#11 // de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/demo/Demo.bla:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

#10 = Class #12 // de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/demo/Demo

#11 = NameAndType #13:#14 // bla:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

#12 = Utf8 de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/demo/Demo

#13 = Utf8 bla

#14 = Utf8 (Ljava/lang/String;)V

So number 7 refers to a String, which refers to an Utf8 blob saying “Hello World”. Likewise number 9 refers to a Methodref which itself refers to 10, 11 etc., which have the class name, method name and type information.

When adding the -l option to the javap invocation, it should print the LineNumberTable as well:

LineNumberTable:

line 6: 0

line 8: 3

line 9: 8

line 11: 13

Equipped with that knowledge, we can now insert our track() method invocations at byte code offsets 0, 3, 8 and 13 … so we’ll end up with something like this:

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

Code:

0: invokestatic #23 // Method de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/coverista/Tracker.track:()V

3: ldc #7 // String Hello World

5: astore_1

6: invokestatic #23 // Method de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/coverista/Tracker.track:()V

9: ldc #7 // String Hello World

11: invokestatic #9 // Method bla:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

14: invokestatic #23 // Method de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/coverista/Tracker.track:()V

17: ldc #15 // String to the blarg

19: invokestatic #9 // Method bla:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

22: invokestatic #23 // Method de/brokenpipe/dojo/undercovered/coverista/Tracker.track:()V

25: return

LineNumberTable:

line 6: 0

line 8: 6

line 9: 14

line 11: 22

… and that’s it 🎉

But wait! After all, how can we actually hook into the byte code loading in the first place?

Java Agents

Since Java 5 there’s a feature called Java Agents, which are explained in the java.lang.instrument Package Docs. There the mechanism is described as follows:

Provides services that allow Java programming language agents to instrument programs running on the JVM. The mechanism for instrumentation is modification of the byte-codes of methods.

Exactly what we need 😏

In contrast to the main method we define in normal application classes, for the agent we need to define a premain method, with the following signature:

public static void premain(String agentArgs, Instrumentation inst)

… and as the name suggests, it’s executed before the actual main method. There might even be multiple agents, in which cases the premain methods are executed in order.

For the agent.jar file to actually work, we need to create a MANIFEST.MF file, declaring a property Premain-Class that points to the name of class, holding the premain method. Afterward we can pass the -javaagent:path/to/agent.jar argument to the java command line. The JRE should then already call premain.

What we do in this premain method is actually up to us. We could mess with the class loader, or we can spin up some threads, monitoring the actual application. We can register shutdown hooks. Or we can just add a transformer, that performs the necessary byte code manipulations.

Our premain method receives an instance of the Instrumentation class, which has this method:

class Instrumentation {

/**

* Registers the supplied transformer.

* @param transformer the transformer to register

*/

void addTransformer(ClassFileTransformer transformer);

}

… and the ClassFileTransformer interface is very straight foward:

interface ClassFileTransformer {

byte[]

transform( Module module,

ClassLoader loader,

String className,

Class<?> classBeingRedefined,

ProtectionDomain protectionDomain,

byte[] classfileBuffer)

throws IllegalClassFormatException

}

… we get a byte[] with the class file contents read from disk, and may return a modified byte[].

So we now know how to register a transformer, that can manipulate the byte code for us. Next step will be to actually come up with an implementation of that thing, that programmatically modifies the byte code array for us.